Tomas Bella, Chief Digital Officer at Dennik N (Photo: Dennik N – Tomas Benedikovic)

The customer journey has fundamentally broken down. The days of direct traffic to a homepage are fading, replaced by random discovery on social platforms. What can news publishers do, and how are the best ones adapting? Find out in this interview with Tomas Bella, Chief Digital Officer of Dennik N.

✨ Listen to the audio version (voiced by AI)

Follow The FatChilli Playbook podcast on Spotify or Apple Podcasts for more insights.

Tomas Bella, Chief Digital Officer of Dennik N, talks in this interview of the Minimum Viable Podcast by Lightning Beetle, a customer experience studio, about the massive transformation of the media landscape, moving from the “golden age” of print advertising to the modern necessity of reader revenue.

With host Michal Blazej, the co-founder of Lighting Beetle, they explored the strategic errors of the past, such as the “pivot to video,” and analyzed the psychology behind why users eventually agree to pay for content.

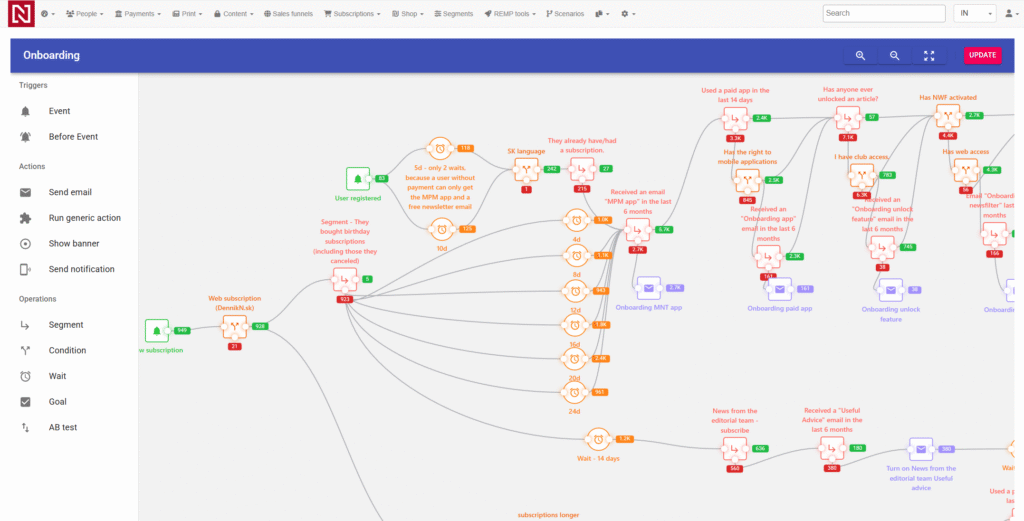

The conversation covered the development of open-source tools like REMP to track subscription metrics, the controversial practice of measuring journalists by sales, and the future impact of TikTok and AI on information consumption.

Tomas also reminded everyone that today’s global subscription behemoth, Piano, was originally started by him in Slovakia as a tiny startup.

We are republishing the entire interview in English, originally conducted in Slovak, with the courtesy of Lighting Beetle, and have made slight edits for clarity.

Michal Blazej: We were once used to buying fresh newspapers in the morning at a newsstand, but today we primarily consume them on mobile. What did that transformation look like? What happened when the media had to transition from print to digital?

Tomas Bella (Dennik N): Two major changes have occurred over the past 20-30 years. The first was the transition from print to online, exactly as you mentioned. The media had their golden age in different countries at different times, but mostly in the 80s, some still in the 90s, when they were cash cows, especially in America, with huge margins, very profitable.

There are legendary stories from that time about journalists who wrote one article a year and were employed, and this was considered normal. If the article was supposed to be good, it needed at least six months or a year because these were enormously profitable media companies.

These times ended with the arrival of the web and the internet, when attention suddenly started shifting from print to online. The decline from print began, and it’s been continuous for the past 20-30 years.

Then there was a second, somewhat less visible change: even on the web, there was what you could call a golden age, when traditional media advertising revenues were large because there wasn’t much competition. Social media didn’t exist yet, and advertising was sold simply; you’d buy 100,000 views or a million views.

With the arrival of social media and many other innovations, advertising revenue from traditional media started declining. This brought the second transformation, from a model where media depended on advertising revenue to a model where an increasing number of them got most of their money from users or readers.

This isn’t really a new model either, in the 70s and 80s, people subscribed to paper newspapers normally, including here. Then the big internet boom came, and we realized that the competition for attention on the web is so fierce, and especially social media’s ability to target advertising is extremely effective, that it’s very hard to compete. It’s also hard to compete in user-generated content and so on.

So many media outlets started returning to the model where they need most of their money from readers, and the higher the quality of the media, the more dependent they tend to be on readers.

For tabloid media, the model of writing articles with huge readership and doing clickbait with massive numbers of views and living off advertising still works. But the more a medium wants to focus on quality, the more it wants to do investigative journalism and so on, the less the advertising model works, and the more it needs reader revenue from subscriptions.

Dead ends and the pivot to video

Were there things you perhaps thought 10-15 years ago would be the future that ultimately didn’t pan out?

There were an incredible number of dead ends. When the big social media platforms appeared, or even when giants like Google emerged, media managers logically didn’t know what was happening, and nobody knew what the future held. Anything new and shiny that appeared, let’s go there.

Many of us were really at the mercy of Facebook’s algorithms. There’s the famous “pivot to video”, a well-known joke in the journalism and publishing industry. At one point, Facebook heavily promoted live video. You might remember a few years ago, everyone was broadcasting live from press conferences, even regular people, simply because Facebook’s algorithm rewarded it with massive reach.

Over the last 20 years, there have been many examples like this, when an algorithm suddenly changed, and it looked like we all had to switch to video and so on.

Of course, people say the original sin of media was giving everything away for free on the internet in the 90s. I don’t think it was a sin; I don’t think anything else could have been done at the time. But many times since then, in the panic of someone eating our lunch, meaning the big tech companies, we rushed to do whatever was currently fashionable. Sometimes it was a video, sometimes a podcast, sometimes something else.

Of course, video and podcasts have their purpose, but as often happens, media overdid it, saying, “Now we’ll only do video because that’s the future.” And then it works for a year or two, and then the algorithm changes, which literally happened with Facebook, live video was no longer what Facebook was pushing, and suddenly you’re left with infrastructure and people doing something that suddenly makes no sense because it no longer brings you readers.

Related article

The story of Piano

The hype has to settle somehow, and then we’ll see what was valuable. You co-founded Piano, and I was thinking about this because I followed Piano very actively, what it was, what you were trying to do, and where it fits into this history. What was your goal?

Some people saw earlier and some later that this shift from advertising revenue to audience revenue was going to happen. I wasn’t the one who saw it first; some people around me did, including the management of SME.sk (Petit Press publishing house) at the time, and the colleague who came up with the Piano idea.

The thought was expressed that this would happen, that as a small Slovak company, we simply wouldn’t be able to compete with Google in how effectively we could sell advertising (back then, it was mainly Google, not Facebook yet), and it would be necessary to build that second pillar where people would also have to pay for content.

We were quite ahead in this compared to Czechia. It’s just the way things are. When you’re still too rich and still making a lot of money, you have less need to think about what will happen in one, two, or three years.

Many other industries before us had gone through this; something that was free suddenly had to be paid for. Those of us who are older remember putting pirated Windows on computers from floppy disks, then there was the Napster era when we pirated audio, and so on. I don’t want to compare since one was illegal and the other legal, but many industries have already gone through this: something that seemed like it should always be free, over many years, it gradually got explained to people that not everything can be free, because that doesn’t make sense. After all, the content won’t exist.

The idea was: let’s create something so it doesn’t take 10 years for a portion of Slovaks to start paying for content and thereby enable quality journalism to continue. So let’s unite several media outlets together, because if everyone explains this at the same time, it will be more effective.

And that’s exactly what happened, and to this day, for example, more Slovaks pay for news content than Hungarians or Czechs, for instance. Thanks to starting earlier, the experience was that the media began explaining earlier why it’s necessary.

Or let me put it this way, people often ask whether I want free media or to pay. I’d prefer free too. But unfortunately, that’s not the question. The question is: do I want more choice and more media and more journalists and higher quality journalism, and I’ll pay for something, or do I want less choice and lower quality journalism and a smaller quantity of journalism, and it’ll be free. These are the two realistic options. And of those two, the first seems better to me; it’s better to have a better choice, even if it sometimes costs 5 euros a month.

Related articles

So Piano evidently fulfilled some historical mission, and it was mainly about showing people the path to paying, or that this is a normal thing. But at the same time, you had that model of combining subscriptions from multiple media into one, and then you kind of moved away from it. That model didn’t work, or what was the problem there?

Yes, that shared subscription concept, we tried to explain it like cable TV, where you just pay and you have many channels included. That concept either fell apart or fulfilled its historical mission, I would say, if I want to put it more nicely.

What few people know is that Piano is now a huge company with hundreds of employees, by far dominant in the global subscription market. Any big media outlet in the world, from Japan to America, that you can think of, is a Piano client. It’s a very successful company, now headquartered in Amsterdam, but because it essentially left Slovakia, few people here know about it anymore.

At the beginning, I told those media outlets: look, let’s do it this way at the start because it will be best for everyone if we do the hardest initial phase all together. And then, if it’s successful, it’s logical that the media will increasingly dislike having to share with someone and not having full control over pricing, where some entity like Piano sets the price and an outlet like the daily Pravda or whoever can’t do anything about it. I wouldn’t like that either if I were in their place.

So it was a logical phase that, in some form, did help us leap ahead in the first few years compared to neighboring countries in how many people started paying. But at some point, the disadvantages started bothering those media outlets more, and many said they’d either stop doing it if they were unsuccessful in that system, or they’d do it themselves because they’d learned enough, and so on.

Global adoption of paid media

Alright, so we’ve talked about Slovakia, where it was perhaps somewhat accelerated by Piano. What does it look like globally? How is the customer gradually getting used to paid media around the world? Are there any regional differences in this?

There are big differences, but mainly it’s determined by how early they started. Because I’ve been dealing with this topic for a long time, I know that 13-15 years ago, we literally experienced this in Switzerland or Norway, where Norwegians told us, I still remember this, a publisher in Oslo told us, “We Norwegians are such that we won’t pay for content on the internet.” And this was literally in one of the richest countries in the world.

Now I experience the same thing when I go to Moldova, or Ukraine, or somewhere in Indonesia, and so on. Every country goes through exactly the same process. At the beginning, everyone thinks that maybe the first successful models were in America, so maybe it works in America, but here it will never work. This was the same in Slovakia, in Czechia, and so on.

What’s important is that we’re not talking about a majority of the population suddenly starting to pay for quality investigative journalism. It’s still a small part of the population, whether 5%, 10%, or 15%; it varies in different countries depending on what developmental stage they’re in. It’s still a more educated part, slightly wealthier part, and so on. Convincing this part is something completely different from convincing the entire population.

This won’t be like “I subscribe to water and I also subscribe to quality newspapers,” if I were to make a comparison. How quickly you manage to convince a relatively elite part of the population, it takes years, but the process is essentially the same in every country. It’s just that somewhere they started earlier and somewhere later.

In Slovakia, especially, it started earlier, and partly thanks to that, for example, in Hungary, now, the process has barely started at all. In Hungary, there are big problems; there are independent media there too, but it was really only one, two, three years ago that independent media first dared to say that you should pay something, otherwise we won’t be able to exist.

There, they’re literally 10 years behind us. You can look at it in various ways, but my view is that if they had started earlier, if they hadn’t persisted with everything having to be free, the independent media could have been stronger because they would have had more resources earlier to fight against the enormous resources of Orbán’s propaganda, for example.

Read also

Why do people pay for content

Do you perceive, or does there exist, some universally applicable process for turning a user into a paying customer? Because you keep repeating that it’s the same principle, that this path is something everyone gradually goes through everywhere?

My favorite saying is that people pay for content when their friends pay for content. First and foremost, no one wants to feel like a fool. When everyone had a pirated copy of DOOM 2, whether on CDs or floppy disks, you wouldn’t buy it because paying for something free made you feel foolish.

Similarly, the first years of Piano were about reversing this: why should I be the only one paying? Overcoming this initial resistance is important, which is why so many media outlets use social proof, telling people in your circle, “Look, this is a person like you, and they’re already paying,” and so on. This is very powerful in those first phases.

Then there are normal methodologies. I just saw something about a new study with six reasons why a person might pay. If I were to simplify it to two, those two are: either I need something, I need the content, or I want to support that medium.

When Dennik N started, 100% of readers were in that second group. 100% of the first 6,000 people who paid us before any product even existed, they just sent us money; it was pure emotion. Something bad was happening, and I wanted to support these journalists who wanted to write independently.

Then, as the product was created and more content was added, sports and so on, it started tipping more toward “I simply need the content.” For example, there might be an article about where I should invest 10,000 euros now if I want more money in 5 years, and I don’t need to have any emotion toward that medium. It doesn’t matter what I think about whether they’re saving democracy or not; I need the content, so I’ll buy it.

Even these two simplifications represent very, very different reasons. Then there’s a whole science around how you gradually need to hit that emotion, which reader is which type, who responds to rational arguments, who responds to “now you must support the press,” how many times someone needs to hit the paywall before paying, and so on. That’s normal e-commerce science around it.

The record-breaking campaign to gain 10k brought in 24k new subscribers

This clearly shows that understanding the customer can really influence the results of that medium.

We ran a campaign in the spring of 2025, where we gained 24,000 new trial subscribers. That seems big here, but really, now wherever I go abroad to conferences, everyone asks about it. It’s possibly the biggest thing in subscriptions in the world that happened in 2025. People keep writing to us asking how we do it.

There were 10 promises of what we would do for Slovakia; it was a kind of public challenge where we said: if you, our subscribers, help us get 10,000 new subscribers, we will do these 10 things. What looked very simple, the hardest part was figuring out which 10 things those people want from us.

It wasn’t that someone sat down and wrote “Let’s make these 10 promises.” We really started by collecting all feedback, everything anyone ever wrote to us by email about why don’t you do this, or I don’t like that, and so on.

One fundamental insight, for example, was that even our subscribers, basically nobody, likes the paywall. That’s such a banal insight, but even people who pay and have no problem paying don’t like that their friends, their grandparents, or people somewhere in Rožňava (a town in eastern Slovakia) don’t want to pay and therefore don’t have access to this information.

This is a fundamental thing that has been repeated for the last 15 years in this field; I’ve been receiving entire emails about this. The people aren’t telling us “I don’t want to pay you,” but “Do something about this problem”, that people have too little information about what’s happening in Slovakia, somewhere there’s theft happening, and they don’t see it because it’s behind a paywall, and so on.

From this came the idea: let’s try to solve this problem for our subscribers. Let’s tell them: fine, please keep paying, but we’ll solve this problem for you. That means we’ll give free subscriptions to all seniors, we’ll give free subscriptions to all young people who sometimes vote for fascists and aren’t well-informed, to all first-time voters, and so on. We’ll really make sure that people who are just slightly disadvantaged, who aren’t in the typical subscriber group, yes, we’ll do everything to get them access because we know you want that.

We formulated some theses about what subscribers want, then about 20 promises emerged, which we then tested. We took a relatively small group of existing subscribers and let them vote on what they’d want Dennik N to do.

For example, it emerged that yes, we should unlock our old texts so people can access investigative stories about what the government did wrong two years ago, and so on. Then we did big calculations about what each promise would cost, because you need to calculate whether unlocking old texts costs us 10,000 or 100,000.

Only through a very long process of comparing what we can afford and what people really, really want from Dennik N did that list of 10 promises emerge. It was a process that took 4-5 months.

Based on that, by precisely hitting what readers imagined we should be doing, solving the problem that troubles them, that yes, I pay, but how does my grandfather get access to information, well here’s a form he can fill out and we’ll send small printed newspapers there for free, by hitting exactly this emotion, it became the most successful campaign not just in Slovakia but anywhere in a wide radius, in subscriptions for many years.

Related articles

Wow, congratulations, that’s basically a textbook design process, I just heard. I’ve read that Dennik N is quite data-driven, but did you follow a design process, or did it happen naturally?

No, we’re not so advanced that we’d know how it’s supposed to be done. It just happened naturally through really long debates. Mostly, we’re very agile, I’d say now, we’re capable of launching a campaign within 24 hours. Someone complained that we give free magazines to schools, so within one day, a big campaign was running about giving magazines to schools, and that people could contribute more.

But this was the first time in 10 years that we were really preparing a campaign half a year in advance and thinking about it every week. There wasn’t any formal process; maybe if we knew one, it would have been better. But just by sitting for a long time and talking about what might work, and talking to many other media outlets, for example, we have one such medium in Denmark with whom we have good cooperation, we took some parts from them, like how to count referrals, gamification of the process where the person knows how many people registered through them and gets thanks for each one.

Some elements were taken from others where we saw it working, and now many are taking this from us. I saw in Croatia, for example, we also have a well-known medium there that’s also exactly 10 years old, about half a year younger than us; they precisely copied this campaign with our permission, including the design, and even translated our exact promises.

But will it work for that local market?

It works! They’re very happy. They’re much, much smaller than us, but literally where we had “all Slovak seniors get something,” they just had “all Croatian seniors get something.” They’re very happy with the result now, and even the design is ours.

The New York Times’ strategy and expansion

That’s localization par excellence,then. Excellent. The New York Times, I think, has special sections where they try to engage people with recipes; they clearly target different audience segments and try to grow the medium. With Dennik N, it’s clear that I’m paying for quality investigative journalism, maybe protection of democratic values; these are the motivations. But these larger media that need to reach multiple segments to maintain healthy cash flow, they’ll probably grow differently, too. What are the possibilities there, and where is the market heading?

Yes, many are already copying that New York Times strategy, and we’ll also have our first game out in a few weeks [it has been launched since], which has been in development for over a year, and I hope it’ll be out soon. The New York Times has Cooking and Games, if I remember correctly, and more than half of their subscribers are now coming via Cooking and Games rather than the news.

So yes, it’s a logical step. They do it very well, but there’s a very fine line where you go too far with the things you’re bundling and start to damage the brand. They manage this very well, but many others who tried, when you throw 20 different unrelated things in there, it can be a problem.

But yes, we’re thinking exactly along these lines too, because the long-term strategy of everyone in the world is to copy the New York Times. And okay, it’ll certainly go in this direction. When they do it, it’ll happen here five years later.

I’m noticing in other industries, too, that an ecosystem of services brings significant profitability. Also, collaborations with other brands, building services that are complementary to my own. I assume media can grow this way too, but as you said, well, the brand is the issue, whether I’ll damage my own brand.

Every brand is a bit different; some can afford to put games or cooking there, and some can’t. We legendarily have no cooking section, probably the only ones in the world, because we didn’t have any idea how to do it better than others. Our long-term strategy has been to only do what we can do better than others, which sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t, but it’s good to at least have that ambition.

That’s why we did political news for a long time and then suddenly started adding sports and psychology and so on. We add these verticals. Each one brings a significant portion of new readers. We don’t write about cars yet, that’s still left, but probably not many others remain.

Then, of course, you come to a point where you don’t just come to work and do nothing this year because you have all the verticals, you start thinking up things like maybe cooking or games, but ideally something that’s neither cooking nor games, something completely new that nobody has thought of yet, but I’ll think of first. But I don’t know what yet.

The changing customer journey

Maybe I’ll go to a different topic now. I recently did a project for SME.sk where we redesigned their mobile homepage, analyzed data, and I was really surprised by how the customer journey has changed. I’m probably still very traditional because I go to the homepage and look at the articles there and then read what interests me; I expect some curation behind that homepage. But most of the traffic comes from social networks.

The second thing I noticed is that most of those people who come to that medium are non-paying customers, from my perspective, headline readers. And when we did qualitative interviews, those people told me that’s how they get their picture of Slovakia, they read the headlines. Which is itself quite a tragedy.

What I wanted to ask is: how has that customer journey changed? How do people find their way to news today if it’s no longer through looking at the homepage and making their own selection of articles to read?

Over the last, let’s say, 10 years, the biggest shift has been from people going to the website, typing Dennikn.sk and looking at the page, to coming randomly to articles, mainly from social media. This was the time of Facebook dominance, where the main landing page was the article itself.

You get into the text, and then there’s this sort of dirty secret of the media: okay, when I have a million or two million unique visitors in audits, I know that the absolute majority of those uniques don’t even know where they were. They just clicked away somewhere in a browser, in the Facebook browser, or something, ended up there once or twice, and didn’t even realize they were there; they just read a bit.

Now, several more scary things are coming for the media at once. First, Facebook is dramatically declining, video is still growing, mainly on Instagram, TikTok, and so on, which generates far fewer click-throughs to websites. Before, we complained that it was so bad because people used to go to the front pages, and now they only come to articles from Facebook; we didn’t like that. Now we won’t even have that; we’ll look back on those as the good old days.

Suddenly, the news consumption for many people means: I saw a video on TikTok, and it doesn’t even occur to me to click through somewhere. Either the editor did it in 15 seconds, told me what’s new, and in the ideal case, I’ll watch that editor’s video, but 90% of the time it’ll be someone else, some influencer or random person who tells them what happened.

And really, for people from our generation, it’s of course a very scary experience to see that people not only watch news on TikTok but even search, I want to know what’s happening with Russia or something, so I’ll search on TikTok for what TikTok videos will show me about what’s happening in Ukraine. This is really happening; these people walk among us, and there’ll be more and more of them. So we’ve come to the topic of how terrible today’s youth is.

At the same time, I think there’ll be a dramatic decline in search, too, as more and more searching happens through AI or chatbots. So, suddenly, even that classic search traffic, when we didn’t like that someone came only through Google and looked at one page and didn’t know where they were, now there’ll be fewer of those people because they’ll find it via ChatGPT. Many of those questions don’t need to go there, like recipes; ChatGPT can do those, too.

So, suddenly, media that have built a strong core of big fans, basically people who pay, will be in a much better position than others. We’re relatively at peace because the people who pay, around 70,000 at the moment, go to our front page or use our app. That core is relatively strong.

But what’s not the core, those let’s say million people monthly who randomly came and suddenly left, that’s extremely shaky now and can really destabilize media that depend on advertising, because that can suddenly just leave. Nobody knows what will happen, but the next few years will be quite turbulent.

The shift to short-form video and social media

Media are somewhat at the mercy of social networks, and social networks now hold all the customers’ attention.

It’s dramatic. Just as we talked about those two fundamental changes before, now the two that are probably coming are: the dramatic shift to short video. For example, two years ago, we had zero people working on social media; we happily survived the first 9 years of Dennik N with zero people doing social media, Facebook just worked, and so on. Now, suddenly, we have 5-6, we’re investing significantly more into it because we have to be where the young people are with those videos.

But yes, this is, my son too won’t go read any article, he’ll just watch a video on Instagram where someone tells him what happened. That’s the first big trend, and we don’t know how far it’ll go, how fast it’ll be, and so on. It’s been going on for some time, but we’re probably not at the peak yet.

Second, what will happen due to AI, nobody knows. I just read that ChatGPT is already among the two or three most visited websites in the world. How fast search via Google will decline and how fast traffic from search engines, which is still significant, will fall, we don’t know. But that could also be a big thing, when suddenly people will search much more through ChatGPT and not through tools that bring traffic to those media.

Most media create personalities from their editors, or I don’t know if most do.

It’s necessary.

Can you monetize that content on social networks? Is the only path still getting them to your website, into your app, turning them into paying customers, that long shot? But directly from the information they put on social networks, that’s not monetizable?

No, well, you can partially monetize YouTube, and the problem is market size. For example, YouTubers in Poland are something completely different than those in Slovakia, because Poland is simply so big that you can be only moderately successful and have enough money to live and do it as a job.

That means even explicitly journalistic projects, where one YouTuber makes quality YouTube videos, that’s a big thing that exists in Poland. Here, just by shrinking the country, when renting a studio costs the same in Slovakia and Poland, but you have 7 times fewer inhabitants, that suddenly completely shifts what’s possible and what makes economic sense.

So, you get some income from YouTube, but not huge, and from Instagram or TikTok, you get basically no income. But what has changed slightly is that for the first time this year, Instagram is a source of conversions too. For years, we said it was really just a cost, and it’s nice to be happy that you have some numbers, but you don’t know what to do with them; you can only feel good that they’re bigger than last month.

Now it can bring conversions too, through the very uncomfortable method of using some software to give that person the link to click through; it’s deliberately made so it can’t really be done, but in the end, it can bring those conversions. But still, it’s much more costly than revenue.

Strategy versus agility

Do you have a medium-term strategy for how you want to innovate, how you want to sell additional services?

There’s a list of many ideas we’d love to have in three months, but won’t get to for two years. So that unintentionally creates a medium-term strategy because tickets are sitting there for two years.

Rather than admitting incompetence for lacking a long-term strategy, I call it agility. Many times, we could react quickly to things that were happening. For example, we launched Czech Deník N in six months from the first idea and Facebook status to launch, and we had no plan at the beginning of that year that in October, we’d have a completely different newspaper in a completely different country.

Same with Czech magazine Respekt, same with some other projects we had, and same with our own internal ones. So yes, we have an idea of how the front page should look different in a year or two, some technologies we’d like to have that we don’t have now, but not a long-term plan, rather a plan to have the structure and culture such that we can react quickly to something that happens or some opportunity we see and seize it more quietly than someone else.

Clever pivot from strategy to agility.

Yes, when you don’t know the strategy, nothing remains but agility.

Dennik N was already created as a digital-first medium. Do silos still exist today in media, between the digital department and the traditional original department, or has it really merged? Has the organizational structure changed, or what state are media in today?

It varies a lot. Starting on a green field is a huge advantage; that’s one thing. The second thing is that just the physical placement of people has enormous significance, and it’s something different when you have 40 people versus 100 or 1,000.

For example, we still have 130 people, all still in one room, nobody has an office, not the director, not me, nobody. And programmers sit literally 2 meters from domestic news. That has enormous significance because when something happens, and people are desperately shouting, the programmers hear that something isn’t working.

At the same time, it’s a person who can stand up, walk three steps, and say: “Why is this like that?” That’s an insane advantage. And that can only be done when they’re physically close. Otherwise, you have to replace it very carefully, and you can’t fully replace it.

And the same is that yes, we had the huge advantage, it was extreme stress and extreme uncertainty, and so on, but when we were created in 2014, we could set it up however we wanted. It was all built on doing online first, and then, as almost an afterthought, every day, someone takes a few hours, scattered throughout the day, to take the best articles that came out and put them in the paper.

If our paper stopped coming out, nothing would happen. Our profit wouldn’t increase or decrease, and we wouldn’t have to fire anyone because nobody works only on paper newspaper. This is, of course, ideal, and like in every industry, whoever starts later does some leapfrogging because they don’t have to get rid of old structures.

Every publisher is very different in how far along they are toward being truly digital first. Everyone has been saying for 15 years that they’re digital first, but now almost everyone is, even though there are still some publishers with large print revenues. But the actual degree of integration and the degree to which editors really care whether their article is in the paper or not, or only on the web, at our place, almost nobody cares about that anymore, but somewhere else, they still might.

The paradox of better UX

I find it surprising that premium American publications like The Economist and similar ones, a whole digital experience is pretty bad, and the subscription service around it is horrible, clicking.

It’s tricky. The Economist is extremely successful on the web, too. It’s a bit deceptive in that, in many ways, you’re hostage to your existing subscribers. Legendarily, our payment window, when you go to subscribe to Dennik N, is very strange, terribly complicated. If I saw it for the first time, I’d say, “I can immediately see 6 fundamental errors and all of this needs to be thrown out immediately, it’s a mess,” and so on.

We worked with Financial Times, we worked with Google, we got feedback from them, and explicitly, a UX expert from Google and FT made us a new window, saying, “You guys there in Eastern Europe don’t know how to do this, this is how it should be.”

And then for about half a year, we worked with them, we explained, showed data, and so on. We have it very precisely calculated. When we put their window into an A/B test that ran for I think 3 months, it cost us about 100,000 euros in lost profit in how much less theirs sold compared to ours.

So simply, the way it’s done now is done that way because we’re constantly running new tests, but customer habit is so strong that we haven’t been able to find a solution that could beat this in an A/B test. We might not like how it is now a hundred times, but when you do it the way it logically should be, according to you, because people are used to something else, you can’t do better.

I’m always cautious, also because I have this experience, that when we look at some website, often it’s incompetence, often many work on terribly old systems, especially American websites on terribly old software that was built for print, and then doesn’t let them put the bundle this way, and it has to be that way. But often it just looks from the outside like it’s not logical at all, but the readers of that specific medium think that’s how it’s logical.

The REMP platform

You received a grant from Google to create a state-of-the-art monetization tool called REMP (Readers’ Engagement and Monetization Platform). It’s an open-source platform used by many publishers around the world. What is it exactly, and how does it help you with monetization and also understanding your users? What data do you collect?

We started building it partly out of necessity, because in 2014, most publishers were still focused on advertising. Most companies that supply software for publishers were also focused on advertising. We needed simple things like a CRM where we’d collect users who pay, and analytics where our editors could see how much each article sells in subscriptions.

We couldn’t find what we needed because everyone at that time, all analytics software, showed page views, and we weren’t interested in page views. We’re not in the page views business, we’re not in the clickbait business. We almost don’t care how many page views we have, not completely, but almost.

So we said okay, we have to make it ourselves, the way a medium focused on reader revenue needs it, so readers are as happy as possible and pay for subscriptions. So we made it ourselves, and then after some time, Google gave those grants for us to open-source everything we had and develop some new features. So basically, they paid for it to be software that anyone in the world can use, rather than just our software.

And further, now 10 developers on our team are still continuously developing it. It’s something we’re completely dependent on because it’s our software, most of our revenue flows through it, but at the same time, many other media around the world use it. For example, in Ukraine, almost all big media use it, but also newspapers in Austria, Germany, and Indonesia, for some reason, big media.

The more a medium needs subscription revenue, the more it needs good software, and ours is quite good, and it’s free. We pay those 10 developers because we need to develop the system for ourselves, and of course, Czech Deník N uses it, Respekt uses it, and basically, other media in our group or where we have some stake.

Then there are system integrators; FatChilli, a Bratislava-based company, does the implementations. When someone contacts us, like this morning, someone from another Indonesian medium wrote to me asking if they can use it. At the beginning, we did those implementations ourselves; now we don’t have the capacity anymore, but there’s a company you can contact. You can always download the source code, it’s open source, and install it yourself, but it’ll be a very painful and long process. So a better process is that an integrator who has already done it on 20 different websites installs it for you, and then you can use it.

That’s what I wanted to ask. I noticed you invested in FatChilli. Was the reason that there was simply too much work for you, and it’s somewhat outside your core business?

We don’t know how to work for clients; our bigger problem is that we work for a client and then forget to bill them for the hours. The company isn’t set up to be able to bill every 15 minutes when someone works on a ticket for some external client. FatChilli knows how to do this and can do those implementations; they make their own modules and so on.

At the same time, they know things we don’t, specifically, programmatic advertising. They manage hundreds or thousands of websites around the world where they handle programmatic advertising. And we said to ourselves, okay, we don’t really understand those ads because our focus is elsewhere, but it’ll be good if someone else understands it and does it.

You mentioned you’re not in the page views business, so advertising revenue isn’t really interesting for you?

It’s still hundreds of thousands of euros, so I wouldn’t say I don’t want them anymore. But in principle, Dennik N would be profitable even if it had zero advertising revenue, which is a very luxurious situation. I’m glad we have that advertising revenue, and I’m happy when it grows, but we’re not existentially dependent on it.

That information flows and data, you mentioned one, what it shows to journalists about how well their individual articles convert. What is that mechanism?

That’s by far the most controversial thing at our place. At a conference once in Germany, a journalist told me that if you did this in Germany, it would be illegal, you’d go to prison. What we do is that everyone at our place knows which article sells how many subscriptions.

I know it’s not so shocking anymore; many media, especially in Scandinavia, do it now. But 5 years ago, nobody did, and even editor bonuses are dependent on how many texts they sell.

What’s important is that this creates a culture where it’s important to me what my customer thinks, what my reader thinks. Because journalists aren’t usually the most humble types. It’s a common problem that “I know how it should be, and nobody’s going to tell me how it should be.” I was a journalist, so I thought that too.

Having that constant feedback that people appreciate, and what’s our enormous luck is that we didn’t know what the data would be when we started doing this. It could have happened that in the previous model, in the previous newspapers, readers would appreciate clickbait. If you put clickbait in the headline, you get lots of page views and thus lots of money. That’s the essence of clickbait.

With subscriptions, we didn’t know if they would appreciate clickbait, but the result is that no. The result is that, in principle, there are now many exceptions, and everyone is unhappy with it. I look at 10 of my texts and think this one should have sold more because it was better, and this one less, and so on, but in principle, it holds that people appreciate quality.

When you work on something for a really long time, or when you find a real investigative story that nobody knew about yet, or when you do a fantastic interview with opinions nobody had read before, there’s some correlation with how it will sell subscriptions.

That means we found a model where, fortunately, the tyranny of the business forces you to do the best possible journalism. That’s the incentive. The motivations of the journalists are aligned with the motivations of the readers, who also want the best possible journalism.

Before, they weren’t aligned at all, which is why I say I’m not interested in page views. If an editor asks how many page views their article has, now they don’t anymore, but 10 years ago, I’d tell them that it shouldn’t concern you. There are many bad ways to achieve lots of page views. There aren’t many tricks you can use if you want 100 people to buy a subscription to your text. It has to be a really exceptional text.

So try to make the best possible text, and readers will basically appreciate it. And that’s the ideal world, because readers force us to do the best possible work.

Do you get a lot of emails? How do you process and aggregate information from that helpdesk or from emails?

First, the helpdesk has to be at important meetings. And this is also something we had to learn. The people who work on the helpdesk are also shareholders in the company. So it’s not some subordinate department or something, or somewhere people would rotate a lot, or there’d be some part-timers there. It’s an important part of the company.

For instance, we would fundamentally not outsource the helpdesk, even though some advise it, because that’s a crucial place from where feedback comes.

Then we do a lot of surveys where we have a very good system connected to our CRM. That means we ask people what they think, do you like this, don’t you like that, and so on, and that data is collected and written, when the person agrees, into that user’s profile. So we can retrospectively say, fine, these people complained that they don’t understand something. I can, in a few clicks, say, Fine, I’ll send them an email now that we’ve fixed what you didn’t like, or Here’s a new feature. That works quite OK.

Local media in a globalized world

One thing I often think about is how, in a globalized world, where text translation isn’t really a problem and media like The Guardian and others provide quality global coverage, how is the role of local media changing? When we have automatic translation, does Dennik N or SME.sk still need to cover a lot about what’s happening in the world? Is that even a topic anymore?

This probably isn’t some super secret, but information about events abroad isn’t what’s most important for most readers. It’s not that newspapers sell because people want to know how the Taiwan crisis is developing. I’m simplifying somewhat; of course, you can write very interestingly and with quality about foreign affairs, and it is being written. But at our place, domestic politics dominates significantly.

And where you wouldn’t expect it, for example, we do a very successful psychology advice column. We tried various things; we even tried adapting something similar from the Washington Post. Even there, even if the problem doesn’t seem localized, that you have an issue with a disobedient teenager or something, that seems like a fairly universal problem, but even there, the localization problem is enormous.

That means when you do a psychology column in Slovakia, it’s much more attractive than when you translate from the Washington Post. We can translate from the Washington Post because we have their license, we can translate whatever we want, and we also have some other licenses. But it’s much less effective than having a Slovak psychologist write it. And we could translate, and someone could do it automatically, but if it worked, we’d do it more, I think we do one text daily or so.

So, if Joe Rogan is hugely popular in America, probably when there’s, which already more or less almost exists, the ability to listen to him in Slovak with automatic translation, he’ll probably find some listeners in Slovakia too. I know many are already doing this, podcasters or YouTubers normally clone their voice. If I were to say where the biggest technological progress in the last year occurred, it’s in how extremely high-quality automatic voice can be. We just switched to a new technology. A year ago, at home, you still needed 50 hours of recordings to train a voice according to you, and now you need two minutes, and it simply generates your voice.

What will certainly happen, as you rightly say, is that big foreign media will offer content in Slovak. But it’s not among my top 10 worries, because Joe Rogan still won’t go to argue with the Slovak prime minister at a press conference. Or write a commentary within ten minutes about what the government just did, or what just happened here somewhere.

Or even just writing about foreign things like Ukraine from a Slovak context, it’s not that easy to just take from German or American newspapers, so it’s good for a Slovak reader. Few people realize this, but when you start doing it, as we have done when translating, you realize that a large part of a journalist’s work is knowing what still needs to be explained and what doesn’t need to be explained. What the reader understands and doesn’t understand, whether you also need to explain where Kyiv is, and so on.

So that’s a large part of the work. I wouldn’t lose sleep over this, as everyone will just read foreign newspapers, which probably won’t happen.

The ultimate design challenge

Finally, I’d like to ask a question I ask every guest. It’s a design question: what is your biggest design challenge? I don’t mean visual design, but rather something you’d like to change, where you see something that needs to move forward? And what’s some challenge, maybe even a life challenge, you’d like to solve?

I don’t know about life, but I’ll tell you a design challenge for Dennik N right now.

For example, we know there’s a problem that many people say they’re tired of this, that you always have politics, that I don’t want to see this person anymore, and you keep having them there, and so on. There’s a terrible conflict between a person’s need to stay sane, because I can’t watch the government members’ press conferences every day, while at the same time having the media’s conviction that we must control government power because that’s what we’re here for, and we have to go there and keep asking them questions, and so on, even though it keeps annoying those readers.

So this sounds like an aesthetic problem, but it’s a design problem, because we really think a lot about when a person comes to our front page, how to demonstrate that we’re doing investigative journalism while at the same time not unnecessarily depressing that person with just “5 things happened, and they’re all bad.”

We don’t have solutions for this; we have some hypotheses, but it’s a long-standing problem. For example, we measured whether, by any chance, political things are too often in the first positions compared to others, given their performance, and so on; some changes were made there.

It’s a fundamental issue because you have one page that can be personalized or not, but you have many different personas, those people who… Even the same person, sometimes I’m in the mood to read what Fico [the Slovak prime minister] said, but sometimes I’m not. And how do you build the product to recognize how much more bad news I can still take, and when I already want to read something positive?

That’s a real big challenge for which we don’t have solutions. We have many different ideas, but none of them is winning yet.

Enjoyed the post? Share it.

FatChilli helps publishers turn audiences into revenue.